http://dx.doi.org/10.15649/2346030X.2587

Pricing and promotion: A literature review.

Sara Aguilar-Barrientos1

Juliana Villegas-Gomez2

Alejandro Arias-Salazar3

- Universidad EAFIT, Medellin – Colombia. E-mail: saguila2@eafit.edu.co Autor de correspondencia

- Universidad EAFIT, Medellin – Colombia.

- Universidad EAFIT, Medellin – Colombia.

Received : July 01, 2021.

Approved: August 18, 2021.

Published: September 1th, 2021.

Abstract— This article intends to carry out a systematic review of the literature on pricing and promotion, as variables that impact profitability in organizations. To achieve this purpose, a systematic review was performed upon the most relevant academic journals (according to Scimago and Country Rank), for the period between 2018 and 2020. The article puts into evidence the correlation between pricing and promotion, as well as the different price-promotion tactics employed by organizations (including coupons, free samples, loyalty programs, discounts and cross selling, among other practices). An array of external factors was also found that affected pricing and promotion performance, making the study more complex. Therefore, despite the correlation existing between the variables at issue, it can be concluded that the success of a price-promotion strategy does not depend exclusively upon itself, but that the results of a monetary discount can be affected by multiple environmental phenomena. Finally, the text concludes with a presentation of certain endogenous factors that can impact the results of price-promotion strategies.

Keywords: Marketing, marketing mix, price-promotion, price, promotion.

Before diving into a search for articles, an extensive list of relevant journals in the field of marketing was drawn up. This list was a result of combining the 2018-2019 Scimago Journal and Country Rank and the classification drawn up by The Chartered Association of Business Schools regarding marketing-related academic publications. The Scimago Journal and Country Rank is an online tool that includes both the journals and certain scientific indicators for the relevant information contained in the Scopus database. It is useful to the extent that it provides a relative quality index, comparing academic journals based on objective criteria such as the amount of times each article gets cited or referenced by other authors or academics and the number of articles published by the journal. It then uses an algorithm to calculate the ranking of each journal relative to the others.

The Chartered Association of Business Schools provides an academic journal guide with some important differentiating factors. The guide is built upon peer-reviews, and an editorial committee evaluates all the journals. The committee goes beyond mere weighted average journal metrics such that the guide reflects the views of the academic community rather than simply enumerating objective metrics. In contrast to The Scimago Journal and Country Rank, the guide created by The Chartered Association of Business Schools considers subjective input, and is relevant insofar as it describes the posture of the academic community towards a publication and takes into account certain non-quantifiable factors.

There are certain aspects were found when using The Scimago Journal and Country Rank together with the guide of The Chartered Association of Business Schools that are worth pointing out. First, neither list is collectively exhaustive, meaning that neither one includes all the journals available to researchers in the field of marketing but only those calculated by the algorithm (in case of The Scimago Rank) and the ones collected by the editorial committee (in case of The Chartered Association of Business Schools guide).

Furthermore, upon comparison, it can be concluded that these lists are not mutually exclusive. This means that the same journal gets ranked divergently upon examination of the different criteria used to assess its quality, academic rigor and relevance to the field of marketing, especially when studying pricing and promotion. Because of this, only the journals ranked in the top ten positions of both rankings were selected to obtain the articles for this literature review.

Thus, the journals selected for performing a search for articles related to pricing and promotions were: European Journal of Marketing, International Journal of Research in Marketing, Journal of Consumer Psychology, Journal of Consumer Research, Journal of Marketing, Journal of Marketing Research, Journal of Retailing, Journal of Business Research, Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, Journal of Economic Psychology and Journal of the Academy of Marketing Research.

The databases used for the search were ScienceDirect, EBSCOhost, Emerald Insight and ISE Web of Science. The key/search terms used in the databases and journals were: pricing, price promotion, promotions, price strategy, promotional methods, price reductions, advertising, price perception, publicity, discounts, and promotional effectiveness.

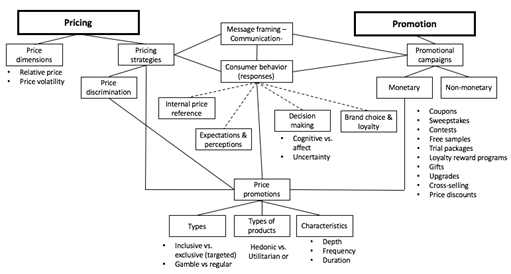

Articles for the last five years were prioritized, and after reading 50 articles of the 70 chosen, the conceptual framework displayed in figure 1 was built to show the main concerns in recent research related to pricing and promotion, the relationships amongst concepts and the intersectional concepts that enable construction of the literature review.

Figure 1: Conceptual framework.

Source: Own preparation.

.

Pricing and promotion are two major marketing mix variables [1], [2]. Pricing is critical because it determines the behavior of both the firm and the consumer, determining the innovation’s profit potential for the former, and for the latter, by representing the cost a customer is willing to pay for certain benefits, and signaling the quality of a good [3]. The objective of promotion, on the other hand, is to directly impact the behavior of the firm’s customers [4]. More specifically, sales promotions intend to create urgency in the minds of shoppers, so they are persuaded to purchase [5], besides improving brand awareness and, in the case of digital organization, increasing indicators like web traffic [6]. Finally, a correct implementation of a price-promotion strategy can lead to benefits for consumers, distributors and manufacturers [7].

But pricing and promotion cannot be studied separately, since both combine to achieve one of the most important goals of the marketing practice, namely, to increase sales [5] which eventually contributes to increased profits for the organization [3], [8]. The implementation of promotions can directly affect price performance. Simple presentation of an economic value and its corresponding discount in a vertical or horizontal format can produce changes in product sales [9]. Additionally, no matter the promotional campaigns implemented, they all result in a perceived change to the regular price of a product [5] even when the price has suffered no modifications, but the promotion promises a discount [10]. Thus, through this intersection of both these marketing mix variables, temporary discounts or price promotions become an important tool, mainly for stimulating purchases or attracting customers to the store, but also for advertising, clearing inventories, passing on manufacturer incentives, and driving store traffic [2], [5], [11], [12].

Sales promotions are pervasive marketing tactics [5], [13] and represent a significant part of a firm’s marketing expenditures [4], [14]. As such, they are an important topic of research for marketing scholars [4], [5], [15], [16]. In this regard, numerous attempts have been made to estimate the effectiveness and impact of price promotions [4], [17]. The reason behind these attempts is the fact that previous research has shown that people have a general tendency to favorably evaluate price promotions [18], and also that specific types of price promotion have given rise to divergent responses and purchasing behaviors in customers [19].

Price promotions are pervasive in consumer markets and customers are often overwhelmed by the various forms of sales promotions offered to them [20]. Close to 50% of a firm’s marketing budget is spent on price-promotion related marketing campaigns [21]. The main reason is because these increase short-term unit sales [22], but there are other aspects in the complex arena of price promotions that are worthy of being researched or studied, such as the types of price promotions implemented [4], [12], [18], the monetization model used [23], the influence of the kinds of products purchased [2], [3], [24]–[30], the product lifecycle [31], the moment of disbursement (prepaid or post-payment) [32], the characteristics of the price promotion strategies [12], [18], [22], [33], [34], the perceptions and expectations of the consumer making the purchasing decision [3], [4], [14], [15], [18], [20], [24], [28], [30], [35]–[37], or the way they are communicated to customers [4], [27], [38].

All these variables are currently on the radar of scholars and research studies, because they can all cause variations within the expected results when price promotions are implemented. This means that common sense says that customers respond positively to price promotions, deriving in increased sales and profits and consumer satisfaction. In the short term, implementation of price-promotion campaigns tend to work, as they reduce the price sensitivity of certain consumers, thus stimulating demand [39]; but there is also counterintuitive evidence regarding the effects of price promotions. Studies covered in this literature review show that not all price promotional campaigns have a positive effect upon increased sales and profits [2], [14], [15], [17]–[19], [26], [28], [40], and do not always create or preserve loyalty [15], [19], [33], [40]. Also, there are results showing a positive view and influence of uncertainty when applying price promotions [20], [36]. Besides, the ongoing use of price-promotions can affect a firm’s brand equity, decreasing the perception of value or quality amongst brands’ consumers [41]. Brand equity is a very important indicator for marketing departments, and a company’s long-term success also depends on it, meaning that this secondary effect can be described as negative [41].

Before delving deeper into each of the elements that make price promotions complex, it is key to start from a more general perspective and describe certain aspects that are important for understanding pricing and promotion. These aspects are: the distinction between promotional campaigns and the place of price promotions within them, and the internal reference price and the way it affects price evaluation. Common forms of promotional campaigns include coupons, price discounts, sweepstakes, contests, free samples [2], [4], trial packages [42], loyalty reward programs [20], [43], gifts [14], [36], one-millionth customer promotions, instant-win promotions, scratch-and-save discount promotions [44], cross-selling promotions [8], [19], upgrades [45], and donation promotions [16]. All campaigns can be categorized as monetary, containing discounts and coupons; or non-monetary, which are the remaining types of campaigns [4]. It is important to mention, regarding monetary and non-monetary promotions, that, apparently, consumers are more influenced to buy with monetary promotions, like price cuts, compared to other types of non-monetary promotions such as additional gifts for purchasing a product [46]. Thus, price promotions are a form of monetary promotion as the promotional incentive in non-monetary promotions is not added to the price of the product [14].

The internal reference price is a concept that serves as a tool to measure whether the price defined for an item is sufficiently attractive for a customer [11], [30]. It is mentally stored and actively constructed [38] and is the result of the empirical generalization that consumers “do not merely judge the absolute price, but evaluate it against reference points” (van Oest, 2013, p. 62), which are constructed based on several factors including previously observed prices or a store’s environment [30]. Kan et al [38] distinguished between External Reference Price (ERP) and Internal Reference Price (IRP), wherein the former refers to the reference price found on the shelves in the product category, and the latter to a reference point based on a recall of previous prices. Therefore, the assumption of having an internal reference price comes from the theory that consumers do not consider the absolute price, but rather evaluate it favorably or not depending on perceived gains or losses when they find it falls below or above an internal point of reference [3], [38].

This is an important concept, because consumer behavior relies on perceptions and expectations [15], [48], so the way customers react to pricing strategies and promotional campaigns depends on how they compare them to their own expectations and the mental relationships they make when valuing the worth of a purchase. Now that the reference price concept and the differences between promotional campaigns are clear, this literature review on pricing and promotions will describe the variables that make the formulation, implementation and evaluation of price promotion a very complex process. Current and upcoming research is studying how customers respond to promotional and pricing strategies to evaluate their effectiveness. This effectiveness relies on the mental frameworks consumers use when buying, on the types of price promotions implemented, on the types of products being purchased, on the way the promotions are communicated, and on the inherent characteristics of the price promotions being offered.

In addition to the internal reference price, consumer responses to promotional stimuli depend on how people process information when buying products. Marketing scholars and psychologists have a classification for two kinds of information processing: cognitive and affective [24], [36], also known as intuitive and deliberate [35] or systematic and heuristic [28]. These two types of thinking have implications for the way consumers behave and respond to price promotion strategies, since affective thinking is automatic and spontaneous, and the cognitive is controlled and meticulous [24]. This means that other aspects such as product quality, price fairness, timing of the offer, and real necessity of the product, among others, come into play when considering a purchase, specifically under cognitive thinking [24], [28], [35].

Affective thinking is more emotional than cognitive thinking [36], which is more objective and analytical [28]. In systematic or cognitive thinking, consumers process information in a methodical, thorough manner; it is more reflective and time consuming. While in the affective or heuristic mode, consumers use short-cut decision making without too much thought [28]. In this regard, Aydinli et al [24] asserted that price promotion discourages deliberation in affective thinking consumers.

Another aspect when studying consumer behavior is the role of uncertainty when analyzing the effectiveness of price promotions and other promotional campaigns. New forms of price promotions are being offered to customers which involve high levels of ambiguity and uncertainty. Some authors have run studies to determine the degree of responsiveness of consumers when there are small probabilities of winning a discount or reward when buying products [11], [20], [36], which perform differently compared to traditional price promotions. Uncertainty refers to events wherein a person is not entirely certain whether they get a promotion in their purchase, because the promotional campaign is designed to not grant the same benefits to all customers [20], [36].

“The term of ambiguity is used to distinguish the class of decisions under uncertainty for which the odds or payoffs are not precisely known” [20]. So ambiguity exists when a customer can only infer the probability of success at between 10 percent and 50 percent [20]. Common wisdom and research in psychology and economics allows inferring that imprecise or inaccurate information regarding price promotions can have a negative effect, because it creates anxiety and purchase likelihood can decrease. However, “recent evidence suggests that people sometimes view uncertainty positively” [36], and even that customers can consider the offer more attractive than a precise one [20]. Laran et al’s study [36] found out that uncertainty is detrimental when the decision is cognitive and positive when the decision is affective.

Nowadays, researchers and managers are exploring the effectiveness of other types of price promotions, which better target the customers they want to reach and innovate in the way in which they are presented to consumers. This may be due to a decreasing effectiveness of traditional price discounts [16]. For instance, the literature contains studies on exclusive or targeted price promotions, which examine “whether consumer response for exclusive deals will be heightened relative to those that are more inclusively available in the marketplace” [18]. Some other forms of price promotions are studied in recent research, such as deals-of-the-day [28], and gambled price discounts [11]. The consolidation of distribution channels like the internet, organizational capacities for segmenting and individualizing consumers thanks to technology, and the development of new retail formats like hard discounts, create new possibilities for price promotions that companies must explore to maintain their effectiveness [49].

Another aspect that interests researchers in marketing are variations in the effectiveness of price promotions related to the types of products offered to customers. The literature suggests that the valuation of price and the way people respond to promotions are influenced by the product to be purchased [29], [30]. This is a critical question that has barely been studied in marketing research: whether and how product category impacts the promotion effectiveness [2]. Regarding the nature of the products purchased, some studies have focused on product accessibility and whether they are top of mind [25]. Others mention the importance of product lifecycle, and how this affects price and customer perception [3]. Additional papers have focused on product categories to identify differences in how people behave towards promotions. These categories are known as utilitarian and hedonic [2], [24], [27]–[29], essential and non-essential [26], or frivolous and practical [29] products. All these terms refer to the same characteristics.

Utilitarian products are mainly instrumental, their consumption is motivated by functional aspects and their value defined by their practicality and utility [2], [28], [29]. This is consistent with the definition of essential products, which are those purchased to fulfill an inherent need [26], and of practical products, that refer to a goal-oriented use [29]. According to literature, when buying utilitarian products, consumers are more likely to incur in more consistent, systematic, and effortful information processing [28].

On the other hand there are hedonic products, defined as multisensory and recognized as sources of fun, pleasure, experiences, and excitement [2], [28], [29]. These are also known as frivolous products, as they are bought for pleasure-oriented uses [29]. Another classification refers to them as non-essential products, because there is no need for them [26]. For the above reasons, and in contrast to utilitarian products, the process and evaluation of information of hedonic products is characterized by being less systematic and effortful [24], [28]. Some authors therefore propose that promotions “have a stronger positive effect on hedonic purchases than on utilitarian purchases” [2].

Another important point when studying price-promotions is the distribution channel through which these are implemented (communications and sales). In the current literature, a large number of studies can be found presenting results for traditional or physical channels. Recent studies show that consumer behavior changes in on-line environments. Thus, the results of the same price-promotion campaign can be different in physical and digital environments [50].

Apropos the way price promotions are communicated, this is an aspect that can make a difference in the responsiveness of customers towards a promotional action. A customer’s perception can be shaped by how a promotion is advertised and the amount of information provided in the promotion at the time of purchase [38]. Also, price promotions are assigned a different value depending on the framing of the message or on the terms used, whether positive or negative, to promote discounts [4]. And price promotions can be perceived as gains by showing odd-endings [27].

Finally, other variables that make the effectiveness of price promotions a very complex phenomenon to study and that have an impact on expected consumer response, are the characteristics of the promotion itself, and more specifically, its depth, frequency and duration [12], [18], [22]. Decisions made about these characteristics, their variations and combinations will contribute to increased sales and profits for the firm. Therefore, during promotion design and implementation, depth must be considered first, defined as the percentage reduction from the existing price [33].

A second aspect to consider is frequency, which is the average number of times a product is promoted over a specific period of time [33]. Research suggests that “frequent price cuts generate more attention from consumers and trigger more elaborate processing and rehearsal” [34]. Regarding frequency, it is important to state that promotion standardization has a positive impact on sales results. In other words, standardizing promotions at retail chains can improve the performance of the marketing campaign, generating more sales and benefits for brands [51]. A third aspect is duration, that refers to the period of time a promotion lasts from the time it is launched and until the product goes back to its regular price [18].

The literature review performed also revealed several studies that help understand the relationship between price promotions and brand choice and loyalty [12], [15], [19], [33], [40]. A price-promotion campaign can be positive or negative for a brand depending on the advertising strategy and message used [52]. From the retailers’ point of view, it is found that they promote strong brands in a more shallow and frequent manner compared to brands with weak loyalty [33], which is consistent with other findings stating that weaker corporate brands are promoted more aggressively [12]. And from the consumer side, it has been found that loyal customers obtain greater discounts on average, which in turn drives customer loyalty [40]. The choice of an appropriate price-promotion strategy can lead to increased customer retention and loyalty [23]. But loyalty can also be hindered when applying price promotions, since they reduce enjoyment and weaken consumption experience over time [15]. Similar findings indicate that ignoring the differences between attitudinal loyalty and habit can “undermine the effectiveness of promotions and even create unintended negative consequences on consumer purchases” [19].

The final conclusions drawn from recent research denote some counterintuitive assertions in the marketing field regarding the effectiveness of price promotions, noting that they are usually effective in the short-term [14], [22], [28], but can have negative effects in the long run [14], [15]. In this regard, monetary promotions are a “key tool to achieve short-term objectives, but can negatively influence other parameters in the long-term, for example, quality perceptions, price sensitivity and brand equity” [14]. Additionally, researchers have found that sales promotions might increase price sensitivity and destroy brand equity over the long term [4].

In order to understand the long-term negative effects of price promotions, a rationale is presented in Buil et al’s work [14] which states that if monetary promotions are run frequently, consumers will become used to having lower prices and will eventually stop buying the product when the promotion concludes [14]. Moreover, research suggests that price promotions might have negative long-term effects on brand sales and consumer loyalty and this can also reduce perceived product efficacy [15]. Product efficacy also relies on the perception of quality, and literature has exhaustively shown that higher prices are indicative of greater product quality [53].

Finally, price promotions have become so important for certain companies that their design and analysis is moving from reactive to proactive [51]. In other words, previously discount campaigns were implemented after product launch to stimulate demand. Currently, some companies, aware of the importance of price promotions for sales and profitability, proactively evaluate and design promotion campaigns, prior even to producing and launching the product or service [51].

In conclusion, all the variables mentioned above must be considered, so current research is building upon the effectiveness of price promotion on customers and firms, and there is still much more to come. According to suggested further research in most papers, scholars should focus on specific price promotion tactics, product specificities, the precise characteristics of promotional discounts, and differentiated decision making processes carried out by customers when purchasing. Consumer behavior is still the most complex aspect studied in marketing research, since “major pressure for changing marketing practices may come from consumers themselves” [54], and especially, because all individuals respond differently to pricing and promotion strategies. Also, most studies covered in this literature review suggest performing further research with larger samples, covering broader categories of products, and considering heterogeneity in consumer preference.

For practitioners, price and promotion determine the success in sales of any organization, which impacts profitability. This review provides current actions taken in this field and the many elements that need to be taken into account when planning, designing, and implementing price-promotion campaigns, in order to guarantee brand equity, sales increase, customers perception and long-term sales performance.

[1] P. Jindal, T. Zhu, P. Chintagunta, and S. Dhar, “Marketing-Mix Response Across Retail Formats: The Role of Shopping Trip Types,” J. Mark., vol. 84, no. 2, pp. 114–132, 2020.

[2] R. Kivetz and Y. Zheng, “The effects of promotions on hedonic versus utilitarian purchases,” J. Consum. Psychol., vol. In press, May 2016.

[3] D. Chandrasekaran, J. W. C. Arts, G. J. Tellis, and R. T. Frambach, “Pricing in the international takeoff of new products,” Int. J. Res. Mark., vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 249–264, Sep. 2013.

[4] E. Gamliel and R. Herstein, “Effects of message framing and involvement on price deal effectiveness,” Eur. J. Mark., vol. 46, no. 9, pp. 1215–1232, Sep. 2012.

[5] W. A. Boland, P. M. Connell, and L.-M. Erickson, “Research Report: Children’s response to sales promotions and their impact on purchase behavior,” J. Consum. Psychol., vol. 22, pp. 272–279, Apr. 2012, doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2011.04.003.

[6] Y. Jiang, Y. Liu, J. Shang, Y. Pinar, and Q. Zhang, “Optimizing online recurring promotions for dual-channel retailers: Segmented markets with multiple objectives,” Eur. J. Oper. Res., vol. 267, no. 2, pp. 612–627, 2018.

[7] Z. Lin, “Price promotion with reference price effects in supply chain,” Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev., vol. 85, pp. 52–68, 2016, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2015.11.002.

[8] S. Li, B. Sun, and A. L. Montgomery, “Cross-Selling the Right Product to the Right Customer at the Right Time,” J. Mark. Res. JMR, vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 683–700, Aug. 2011.

[9] S. Feng, R. Suri, M. C.-H. Chao, and U. Koc, “Presenting comparative price promotions vertically or horizontally: Does it matter?,” J. Bus. Res., vol. 76, pp. 209–218, 2017, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.01.003.

[10]Y. Deng, R. Staelin, W. Wang, and W. Boulding, “Consumer sophistication, word-of-mouth and ‘False’ promotions,” J. Econ. Behav. Organ., vol. 152, pp. 98–123, 2018, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2018.05.011.

[11]S. Alavi, T. Bornemann, and J. Wieseke, “Gambled Price Discounts: A Remedy to the Negative Side Effects of Regular Price Discounts,” J. Mark., vol. 79, no. 2, pp. 62–78, Mar. 2015.

[12]J. Empen, J.-P. Loy, and C. Weiss, “Price promotions and brand loyalty: Empirical evidence for the German ready-to-eat cereal market,” Eur. J. Mark., vol. 49, no. 5/6, pp. 736–759, May 2015.

[13]R. R. Vadamala and B. Amarnath, “An Empirical Study on the Effectiveness of Consumer Sales Promotion Tools in Hyderabad,” J. Bus. Strategy, vol. 17, no. 3, 2020.

[14]I. Buil, L. De Chernatony, and T. Montaner, “Factors influencing consumer evaluations of gift promotions,” Eur. J. Mark., vol. 47, no. 3/4, pp. 574–595, Mar. 2013.

[15]L. Lee and C. I. Tsai, “How Price Promotions Influence Postpurchase Consumption Experience over Time,” J. Consum. Res., vol. 40, no. 5, pp. 943–959, Feb. 2014.

[16]K. P. Winterich, R. E. Carter, M. J. Barone, R. Janakiraman, and R. Bezawada, “Tis better to give than receive? How and when gender and residence-based segments predict choice of donation- versus discount-based promotions,” J. Consum. Psychol., vol. 25, pp. 622–634, Oct. 2015.

[17]S. Ray, C. A. Wood, and P. R. Messinger, “Multicomponent Systems Pricing: Rational Inattention and Downward Rigidities,” J. Mark., vol. 76, no. 5, pp. 1–17, Sep. 2012.

[18]M. J. Barone and T. Roy, “The effect of deal exclusivity on consumer response to targeted price promotions: A social identification perspective,” J. Consum. Psychol., vol. 20, pp. 78–89, Jan. 2010.

[19]Y. Liu-Thompkins and L. Tam, “Not All Repeat Customers Are the Same: Designing Effective Cross-Selling Promotion on the Basis of Attitudinal Loyalty and Habit,” J. Mark., vol. 77, no. 5, pp. 21–36, Sep. 2013.

[20]Q. Yao, R. Chen, and P. Zhao, “Precise versus imprecise promotional rewards at small probabilities: Moderating from purchase value and promotion budget,” Eur. J. Mark., vol. 47, no. 5/6, pp. 1006–1021, May 2013.

[21]S. Bogomolova, M. Szabo, and R. Kennedy, “Retailers’ and manufacturers’ price-promotion decisions: Intuitive or evidence-based?,” J. Bus. Res., vol. 76, pp. 189–200, 2017, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.05.020.

[22]J. G. Dawes, “Brand-Pack Size Cannibalization Arising from Temporary Price Promotions,” J. Retail., vol. 88, pp. 343–355, Sep. 2012.

[23]J. Kim, “The impact of different price promotions on customer retention,” J. Retail. Consum. Serv., vol. 46, pp. 95–102, 2019, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.10.007.

[24]A. Aydinli, M. Bertini, and A. Lambrecht, “Price Promotion for Emotional Impact,” J. Mark., vol. 78, no. 4, p. 80, Jul. 2014.

[25]J. Berger and E. M. Schwartz, “What Drives Immediate and Ongoing Word of Mouth?,” J. Mark. Res. JMR, vol. 48, no. 5, p. 869, Oct. 2011.

[26]F. Cai, R. Bagchi, and D. K. Gauri, “Boomerang Effects of Low Price Discounts: How Low Price Discounts Affect Purchase Propensity,” J. Consum. Res., vol. 42, no. 5, pp. 804–816, Feb. 2016.

[27]J. Choi, Y. Li, P. Rangan, P. Chatterjee, and S. Singh, “The odd-ending price justification effect: the influence of price-endings on hedonic and utilitarian consumption,” J. Acad. Mark. Sci., vol. 42, no. 5, p. 545, Sep. 2014.

[28]M. Eisenbeiss, R. Wilken, B. Skiera, and M. Cornelissen, “What makes deal-of-the-day promotions really effective? The interplay of discount and time constraint with product type,” Int. J. Res. Mark., vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 387–397, Dec. 2015.

[29]U. R. Karmarkar, B. Shiv, and B. Knutson, “Cost conscious? The neural and behavioral impact of price primacy on decision making,” J. Mark. Res., vol. 52, no. 4, pp. 467–481, 2015.

[30]J. H. Park, D. L. MacLachlan, and E. Love, “New product pricing strategy under customer asymmetric anchoring,” Int. J. Res. Mark., vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 309–318, Dec. 2011.

[31]X. Xu, R. Chen, and J. Zhang, “Effectiveness of trade-ins and price discounts: A moderating role of substitutability,” J. Econ. Psychol., vol. 70, pp. 80–89, 2019, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2018.10.007.

[32]R. K. Sinha and A. Adhikari, “Buyer-seller amount-price equilibrium for prepaid services: Implication for promotional pricing,” J. Retail. Consum. Serv., vol. 44, pp. 285–292, 2018, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.07.020.

[33]W. J. Allender and T. J. Richards, “Brand Loyalty and Price Promotion Strategies: An Empirical Analysis,” J. Retail., vol. 88, pp. 323–342, Sep. 2012, doi: 10.1016/j.jretai.2012.01.001.

[34]C. J. S. Lourenço, E. Gijsbrechts, and R. Paap, “The Impact of Category Prices on Store Price Image Formation: An Empirical Analysis,” J. Mark. Res. JMR, vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 200–216, Apr. 2015.

[35]R. Dhar and M. Gorlin, “A dual-system framework to understand preference construction processes in choice,” J. Consum. Psychol., vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 528–542, Oct. 2013.

[36]J. Laran and M. Tsiros, “An Investigation of the Effectiveness of Uncertainty in Marketing Promotions Involving Free Gifts,” J. Mark., vol. 77, no. 2, pp. 112–123, Mar. 2013.

[37]R. Suri, K. Monroe, and U. Koc, “Math anxiety and its effects on consumers’ preference for price promotion formats,” J. Acad. Mark. Sci., vol. 41, no. 3, pp. 271–282, May 2013.

[38]C. Kan, D. R. Lichtenstein, S. J. Grant, and C. Janiszewski, “Strengthening the Influence of Advertised Reference Prices through Information Priming,” J. Consum. Res., vol. 40, no. 6, pp. 1078–1096, Apr. 2014.

[39]M. Nagare and P. Dutta, “Single-period ordering and pricing policies with markdown, multivariate demand and customer price sensitivity,” Comput. Ind. Eng., vol. 125, pp. 451–466, 2018, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2018.09.004.

[40]J. Wieseke, S. Alavi, and J. Habel, “Willing to Pay More, Eager to Pay Less: The Role of Customer Loyalty in Price Negotiations,” J. Mark., vol. 78, no. 6, pp. 17–37, Nov. 2014.

[41]P. Valette-Florence, H. Guizani, and D. Merunka, “The impact of brand personality and sales promotions on brand equity,” J. Bus. Res., vol. 64, no. 1, pp. 24–28, 2011, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.09.015.

[42]H. Datta, B. Foubert, and H. J. Van Heerde, “The Challenge of Retaining Customers Acquired with Free Trials,” J. Mark. Res. JMR, vol. 52, no. 2, p. 217, Apr. 2015.

[43]J. Zhang and E. Breugelmans, “The Impact of an Item-Based Loyalty Program on Consumer Purchase Behavior,” J. Mark. Res. JMR, vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 50–65, Feb. 2012.

[44]L. Jiang, J. Hoegg, and D. W. Dahl, “Consumer Reaction to Unearned Preferential Treatment,” J. Consum. Res., vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 412–427, Oct. 2013.

[45]W. Mao, “Sometimes ‘Fee’ Is Better Than ‘Free’: Token Promotional Pricing and Consumer Reactions to Price Promotion Offering Product Upgrades,” J. Retail., vol. 92, no. 2, pp. 173–184, Jun. 2016.

[46]B. Foubert, E. Breugelmans, K. Gedenk, and C. Rolef, “Something Free or Something Off? A Comparative Study of the Purchase Effects of Premiums and Price Cuts,” J. Retail., vol. 94, no. 1, pp. 5–20, 2018, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2017.11.001.

[47]R. Van Oest, “Why are Consumers Less Loss Averse in Internal than External Reference Prices?,” J. Retail., vol. 89, no. 1, pp. 62–71, Mar. 2013.

[48]F. Shaddy and L. Lee, “Price Promotions Cause Impatience,” J. Mark. Res. JMR, vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 118–133, 2020, doi: 10.1177/0022243719871946).

[49]T. Kuntner and T. Teichert, “The scope of price promotion research: An informetric study,” J. Bus. Res., vol. 69, no. 8, pp. 2687–2696, 2016, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.11.004.

[50]J. R. Carlson and M. Kukar-Kinney, “Investigating discounting of discounts in an online context: The mediating effect of discount credibility and moderating effect of online daily deal promotions,” J. Retail. Consum. Serv., vol. 41, pp. 153–160, 2018, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.12.006.

[51]F. Morimura and Y. Sakagawa, “Information technology use in retail chains: Impact on the standardisation of pricing and promotion strategies and performance,” J. Retail. Consum. Serv., vol. 45, pp. 81–91, 2018, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.08.009.

[52]I. Buil, L. de Chernatony, and E. Martínez, “Examining the role of advertising and sales promotions in brand equity creation,” J. Bus. Res., vol. 66, no. 1, pp. 115–122, 2013, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.030.

[53]D. Yan, J. Sengupta, and Jr. Wyer Robert S., “Package size and perceived quality: the intervening role of unit price perceptions,” J. Consum. Psychol., vol. 24, pp. 4–17, Jan. 2014.

[54]P. Kotler, “Reinventing Marketing to Manage the Environmental Imperative,” J. Mark., vol. 75, no. 4, p. 132, Jul. 2011.