VOL. 11 Nº ENERO – ABRIL 2020 BUCARAMANGA, COLOMBIA

E-ISSN: 2346-3414

Rev Cuid. 2020; 11(1): e851

http://dx.doi.org/10.15649/cuidarte.851

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Pleasure and suffering indicators in primary healthcare workers in Brazil

Prazer e sofrimento em trabalhadores da atenção primária à saúde do Brasil

Placer y sufrimiento en trabajadores de atención primaria en salud de Brasil

Graziele de Lima Dalmolin1, Taís Carpes Lanes2, Ana Carolina de Souza Magnago3, Caroline Setti4, Julia Zancan Bresolin5, Katiane Sefrin Speroni6

1Federal University of Santa Maria, Santa Maria, Brazil. E-mail: grazi.dalmolin@gmail.com https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0985-5788.

2Federal University of Santa Maria, Brasil. Corresponding Author. E-mail: taislanes_rock@hotmail.com https://orcid.org/0000- 0001-9337-7875

3Federal University of Santa Maria, Santa Maria, Brasil. E-mail: anasmagnago@gmail.com https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4902-4110

4Federal University of Santa Maria, Santa Maria, Brasil. E-mail: carolinesho@hotmail.com https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9635-8311

5Federal University of Santa Maria, Santa Maria, Brasil. E-mail: juliabresolin@hotmail.com https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4773-0460

6Federal University of Santa Maria, Santa Maria, Brasil. E-mail:katiane.speroni@gmail.com https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6815-1559

Historical Information

Received: April 18th, 2019

Accepted: September 30th, 2019

How to cite this article: Dalmolin GL, Lanes TC, Magnago ACS, Setti C, Bresolin JZ, Speroni KS. Prazer e sofrimento em trabalhadores da atenção primária à saúde do Brasil. Rev Cuid. 2020; 11(1): e851. http://dx.doi.org/10.15649/cuidarte.851

![]() ©2020 Universidad de Santander. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution license (CC BY-NC 4.0), which allows unlimited use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are duly cited

©2020 Universidad de Santander. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution license (CC BY-NC 4.0), which allows unlimited use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are duly cited

Abstract

Introduction: The assessment of pleasure and suffering indicators in primary healthcare workers gains relevance due to the complexity of multi-professional working and the close link between community and team. Therefore, this study aimed at assessing the pleasure and suffering indicators in primary healthcare workers from a municipality in Southern Brazil. Materials and Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted with 218 workers in 34 primary healthcare units. Data was collected from March to August 2015 using the Pleasure and Suffering Indicators at Work Scale (PSIWS) and analyzed through descriptive statistics and association tests. Results: The factors indicating suffering, professional burnout and lack of recognition were evaluated as critical, unlike those of pleasure, where only professional fulfillment was classified as critical and freedom of expression as satisfactory. Among these indicating factors, the following showed better averages: pride in what I do, cooperation with colleagues, stress and indignation at work. Discussion: Workers are satisfied and proud of the work they do and feel free to share their thoughts and ideas with the team, although exhausted and little recognized for their actions. Conclusions: It can be concluded that professional burnout, stress, indignation and lack of recognition are indicators of suffering at work while freedom of expression, pride in what you do and cooperation with colleagues are sources of pleasure.

Key words: Pleasure; Stress, Psychological; Primary Health Care; Occupational Health.

Resumo

Introdução: A avaliação dos indicadores de prazer e sofrimento em trabalhadores da Atenção Primária à Saúde se torna relevante em decorrência à complexidade do trabalho multiprofissional e ao vínculo estreito entre a comunidade e equipe. Assim, o objetivo deste estudo é avaliar os indicadores de prazer e sofrimento em trabalhadores da Atenção Primária à Saúde de um município do Sul do Brasil. Materiais e Métodos: Estudo transversal realizado com 218 trabalhadores em 34 unidades da Atenção Primária à Saúde. A coleta de dados ocorreu de março a agosto de 2015, por meio da Escala de Indicadores de Prazer-Sofrimento no Trabalho. Para análise dos dados, utilizou-se estatística descritiva e testes de associação. Resultados: Os fatores indicadores de sofrimento, esgotamento profissional e falta de reconhecimento foram avaliados como críticos, e os de prazer, realização profissional classificado como crítico e liberdade de expressão como satisfatória. Dentre esses fatores indicadores, apresentaram maiores médias: orgulho do que faço, solidariedade com os colegas, estresse e indignação com o trabalho. Discussão: Os trabalhadores estão satisfeitos e orgulhosos com o trabalho e se sentem livres em expor seus pensamentos e ideias com a equipe, porém esgotados e pouco reconhecidos pelas ações que realizam. Conclusões: Pode-se concluir que o esgotamento profissional, estresse, indignação e a falta de reconhecimento são indicadores de sofrimento no trabalho. A liberdade de expressão, orgulho do que faz e solidariedade com os colegas são fontes de prazer.

Palavras chave: Prazer; Estresse Psicológico; Atenção Primária à Saúde; Saúde do Trabalhador.

Resumen

Introducción: La evaluación de los indicadores de placer y sufrimiento en trabajadores de Atención Primaria en Salud gana relevancia a raíz de la complejidad del trabajo multiprofesional y al vínculo estrecho entre comunidad y equipo. De esta forma, el objetivo de este estudio es evaluar los indicadores de placer y sufrimiento en trabajadores de Atención Primaria en Salud de un municipio del Sur de Brasil. Materiales y Métodos: Estudio transversal realizado con 218 trabajadores en 34 unidades de Atención Primaria en Salud. La recolección de datos se llevó a cabo desde marzo a agosto de 2015, utilizando la Escala de Indicadores de Placer-Sufrimiento en el Trabajo. El análisis de los datos se hizo a través de estadística descriptiva y pruebas de asociación. Resultados: Los factores indicadores de sufrimiento, agotamiento profesional y falta de reconocimiento fueron evaluados como críticos, a diferencia de los de placer, donde solo el de realización profesional se clasificó como crítico y el de libertad de expresión como satisfactorio. Entre estos factores indicadores, presentaron mejores promedios: orgullo por lo que hago, solidaridad con los colegas, estrés e indignación con el trabajo. Discusión: Los trabajadores están satisfechos y orgullosos del trabajo y se sienten libres de exponer sus pensamientos e ideas con el equipo, aunque agotados y poco reconocidos por las acciones que realizan. Conclusiones: Se puede concluir que el agotamiento profesional, el estrés, la indignación y la falta de reconocimiento son indicadores de sufrimiento en el trabajo. La libertad de expresión, enorgullecerse de lo que se hace y la solidaridad con los colegas son fuentes de placer.

Palabras claves: Placer; Estrés Psicológico; Atención Primaria de Salud; Salud Laboral.

INTRODUCTION

Over the years, work activity has become a priority in social insertion and personal satisfaction, which is influenced by the way work is set up. From this perspective, work organization is responsible for the experience of pleasure and suffering as it comprises a social relationship that integrates both ethical issues and rules to control workforce1,2.

Thus, work organization influences the vulnerability of workers to professional illness. These risks stem from days of intense work, little time to perform tasks, repetitive and tiring activities, with little autonomy to express themselves and reflect on the services provided1.

The psychodynamics of work, involving the relationship between suffering and pleasure, establishes the non-neutrality at work interfering with workers’ mental health3.

To assist in coping with suffering, it is important to use collective and individual strategies to maintain or recover health3. From this perspective, the work process is surrounded by the dynamics of human relationships and work organizations that influence the feeling of pleasure and suffering3.

Pleasure at work is understood as the subjective way in which a worker deals with situations that cause suffering without neglecting it2. However, pleasure is also associated with work achievement, in the face of pride in the worker’s profession and role recognition. It should be noted that pleasure can also be associated with the worker’s autonomy since the planning and implementation of activities make their relationships more pleasant and supportive among colleagues4,6.

The feeling of suffering arises from conflicting situations in organizations, which makes workers seek ways to tackle it in a constant search for satisfaction and pleasure at work. The experience of suffering may indicate that defensive strategies are not enough to overcome it, which influences the incidence rate of work illnesses7,3.

It is important to assess pleasure and suffering among primary health care (PHC) workers as it is a place of access for people with high user demands, lack of human resources, overload, and fast-paced work environment7. These workers make up the link and bond between the team and the community to promote comprehensive care, in view of the care provided and users’ reception7.

PHC provides assistance to users, both individually and collectively, which includes health promotion and protection. In light of these characteristics, professionals involved and committed to the health of the PHC population are vulnerable to the risk of illness7. The suffering of these workers may result from PHC structure, in which serves users from different socioeconomic contexts. In this case, the proximity to the community and the recognition of its vulnerabilities and precariousness are noted, which may lead professionals to experience a feeling of helplessness in the face of existing problems. Many times, social and health situations are adverse whose coexistence with local problems and involvement with the community may lead to suffering7.

Considering the aspects addressed, a search was performed in the Virtual Health Library (VHL) using the descriptors pleasure, suffering, and primary health care during the project preparation period and updated in September 2019. Seven articles were found, in which it was observed that the indicators of pleasure, professional achievement, and freedom of expression were classified as satisfactory and the indicators of suffering, professional burnout, and lack of recognition were classified as critical and satisfactory, respectively7.

Recognition and freedom of expression when satisfactory can help enhance professional achievement and influence the reduction of professional burnout7, making it necessary to evaluate them in the workplace. In addition, it was observed that few studies have discussed the subject of pleasure and suffering in PHC health workers.

Thus, the evaluation of pleasure and suffering indicators in PHC workers becomes relevant as a result of the complexity of multidisciplinary work and the close link between the community and team. Therefore, based on the research question “What are the indicators of pleasure and suffering in Primary Health Care workers in a Southern Brazilian municipality?”, the objective was to evaluate the indicators of pleasure and suffering in Primary Health Care workers in a municipality in Southern Brazil.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A cross-sectional study was conducted in all Primary Health Care units in a Southern Brazilian municipality. The total number of municipal PHCs is 34 health care units, 19 of which are Basic Health Units (BHU) and 13 are Family Health Strategies (FHS). Two health care units are defined as mixed due to the process of reorganization and re-structuring of PHC teams in the municipality. The mixed units have two teams working in assistance.

The population of this study considered all PHC workers of the municipality under study. For statistical purposes, a non-probabilistic sample was considered for convenience. However, to reduce the occurrence of possible biases, a sample calculation with a finite population was used to estimate the lowest number of subjects.

20% of the total population was added to ensure and enable the performance of statistical tests. Thus, with a population of 332 workers, 95% confidence interval and 0.05 p-value, a minimum of 179 participants was estimated. All workers who were in their workplaces during data collection were invited to participate, so at the end of the collection, the sample consisted of 218 participants.

Inclusion criteria were to be a PHC onsite worker over the last six months at least. All workers that were on leave from work due to any reason during the period of data collection were excluded.

For data collection, sociodemographic and work characterization instruments were used (gender, age, number of children, workplace, profession, education, salary satisfaction, degree of satisfaction with work, work shift, employment relationship, other employment and average length of service) and Pleasure and Suffering Indicators at Work Scale (PSIWS).

The PSIWS scale is one of the subscales of the Inventory on Work and Risk of Illness (ITRA), which assesses the dimensions of interrelations between work and illness risk3. The PSIWS is composed of 32 items divided into four factors, two factors evaluating pleasure: professional achievement (questions 9 to 17) and freedom of expression (questions 1 to 8), and two factors evaluating suffering: professional burnout (questions 18-24) and lack of recognition (questions 25 to 32). The PSIWS factors are considered universal factors of the experiences of pleasure and suffering according to the Psychodynamics of Work, a theory that supports an instrument verified by its elaboration and validation processes in Brazil3.

A Likert-type scale withseven points varying from 0 = never; 1 = once; 3 = three times; 4 = four times; 5 = five times to 6 = six or more times was used. The purpose of PSIWS is to evaluate the experiences of pleasure and suffering indicators over the last six months3. In the PSIWS scale, the following parameters are considered as results for pleasure experience: above 4.0 = mostly positive, satisfactory assessment; between 3.9 and 2.1 = moderate, critical assessment and below 2.0 = rarely severe assessment. For suffering factors, the analysis should be based on the following levels: above 4.0 = mostly negative, severe assessment; between 3.9 and 2.1 = moderate, critical assessment; and below 2.0 = less negative, satisfactory assessment.

Data collection was carried out by previously trained data collectors from March to August 2015, Monday to Friday day shift. Before starting data collection, it was agreed with the coordinators of the health care units to schedule collections so as not to hinder workflow. All health workers in each PHC units were invited to participate in the study receiving guidance regarding the research objectives, and those who agreed to participate signed the Informed Consent Form in two copies, and completed individually the instrument at the workplace during working hours.

Data were entered in Microsoft Excel® with double independent typing and verification of errors and inconsistencies by two typists. Afterward, data analysis was performed in PASW Statistics® (Predictive Analytics Software, SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) version 21.0 for Windows.

Categorical variables were analyzed using absolute (n) and relative (%) frequency. Quantitative variables were analyzed by means of position and dispersion measures, using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test or Pearson’s coefficient of variation. Bivariate analyses were performed using the t-test on variables of up to two groups and ANOVA for more than two groups with a 95% confidence interval. The internal consistency of factors was verified by Cronbach's alpha, accepting values above 0.70 as reliable.

For the development of this research, ethical aspects of Resolution 466/12 of the National Health Council were reviewed and followed8. The research was approved by the Continuing Health Education Center in the Municipality under study, receiving a favorable opinion from the Research Ethics Committee (REC) of the Federal University of Santa Maria, under code number CAAE 40264314.4.0000.5346 dated January 12th, 2015.

RESULTS

The PHC staff in the municipality of this study consists of 332 workers, of which 10.8% (n = 36) were on leave for health-related treatment or vacation. The eligible population was 296 participants, 16.2% (n = 48) refused to participate in the study and 9.5% (n = 28) could not be located or did not the return the instrument. Thus, 220 workers participated in the study, but 2 instruments were excluded because they were incomplete. The total sample consisted of 65.7% (n=218) of PHC workers.

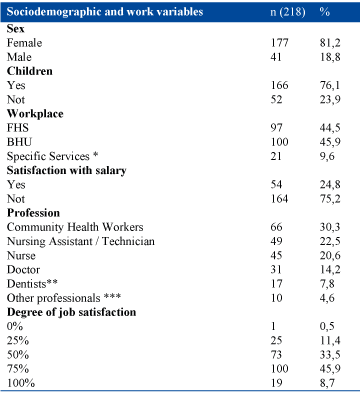

The sample was characterized by sociodemographic and work data, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and work data of Primary Health Care workers.

Santa Maria - RS, Brazil, 2019

Source: Authors’ database (2015).

* Characterized as Primary Care Coordination Service and Health Care Secretariat; ** Dental Assistants and Dentists; *** Social workers, psychologists, speech therapists, pharmacists, and physiotherapists.

Most of workers were female in 81.2% (n = 177), mean age was 42.8 years (Standard Deviation = 10.4) and number of education years ranged from 0 to 10 years in 48.6% (n = 106). As for work variables, morning and afternoon work shifts were predominant in 83.9% (n = 183), 90.4% of workers have open-ended contracts (n = 197) and 18.8% have another job (n = 41). The average time of workers serving at the PHC was of 8.7 years (Standard Deviation = 8.6), 7.3% suffered work accident (n = 16) and 18.8% stopped working due to health reasons (n = 41).

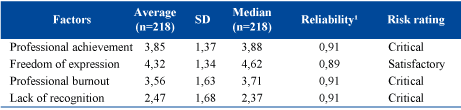

Table 2, shows the descriptive statistical mean, median, and standard deviation factors as well as the reliability coefficient and PSIWS factor classification.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics, Cronbach's alpha, and risk classification according to factors of Pleasure and Suffering Indicators Scale. Santa Maria - RS, Brazil, 2019

Source: Authors’ database (2015).

¹ Cronbach alpha of the 32-item instrument = 0.85.

As for the assessment of workers, three PSIWS factors were considered critical, such as professional achievement, professional burnout and lack of recognition. Only the freedom of expression factor was considered satisfactory.

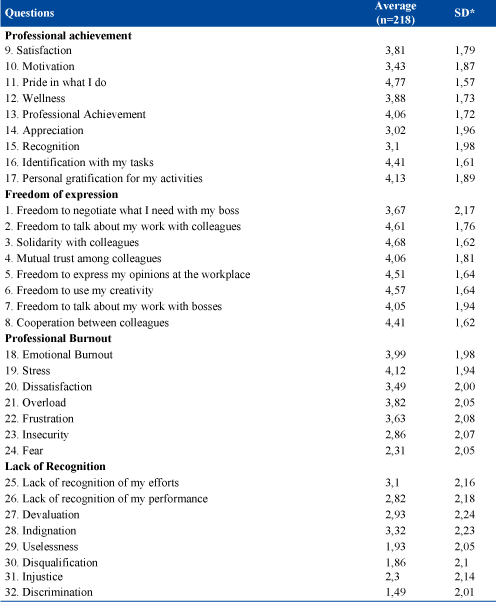

Table 3, shows the descriptive data of each scale item.

Table 3. Items of the Pleasure and Suffering Indicators at Work Scale, Mean and Standard Deviation. Santa Maria - RS, Brazil, 2019

Source: Authors’ Database (2015).

* SD: standard deviation.

The highest averages in the indicators of pleasure, professional achievement and freedom of expression were, respectively: "pride in what I do " and " solidarity with colleagues”. In relation to the suffering indicator factors, professional burnout had the highest average for “stress” and a lack of recognition for “indignation”.

Table 4 shows the association between PSIWS factors and sociodemographic/work variables.

Table 4. Association between the factors of the Pleasure and Suffering Indicators at Work Scale and the sociodemographic and work variables of Primary Health Care workers. Santa Maria - RS, Brazil, 2019

Source: Authors’ Database (2015).

* Significant associations (p <0.05).

When comparing the average between the PSIWS factors and sociodemographic-work variables, statistical difference was found between the professional burnout factor in women, number of education years of up to five years, work accidents and professional community health workers. The other two factors, professional achievement and lack of recognition, were related only to the work-related accident variable.

DISCUSSION

The service environment triggers experiences of both pleasure and suffering, depending on how healthy internal relations are. These relationships enable workers to practice health care based on behavior and actions considered safe to users3,9.

Thus, the risks of illness related to experiences of pleasure and suffering are perceived during PHC work process and cannot be studied separately3.

The proposed study found that 45.9% of workers have a 75% degree of job satisfaction, which may be a reflection of a united team that encourages professional and personal growth and that is concerned with listening to their colleagues. Nevertheless, a study conducted with health workers working in family health units in Coimbra rated 71.5% in job satisfaction10.

It is noteworthy to keep workers satisfied and to be able to identify, in periodic team meetings, possible problems that help trigger suffering1. Based on its identification, it is possible to refer workers to specialized professionals for their evaluation and diagnosis and after that, return with resolutive feedback.

As for risk classification, workers considered critical the factors of professional achievement, burnout and lack of recognition. Taking into account that these workers had an average number of education years between 0 and 10 years, it is controversial compared with the literature as the presence of professional burnout usually occurs in workers with more education12.

A strong indication is that people, when starting their careers, tend to be more critical of their work and create expectations related to professionals’ growth in their process. However, when it is not achieved, these may cause suffering and sadness, which workers cannot cope with, resulting in psychological and emotional burnout7.

It is important to point out that these factors assessed as critical may also be associated with working conditions. The challenge of providing quality assistance to users in the face of difficulties is huge. Workers that are usually unable to perform their activities as they should may increase their exposure to risks of illness13.

The freedom of expression factor was classified as satisfactory in accordance with a study conducted in Primary Care in Southern Brazil, which assessed it as satisfactory7. This allows us to infer that workers have the freedom to express themselves in work teams7.

Freedom of expression can be understood as the way of discussing, expressing opinions and reflecting on various issues among a group of people13, which is related to cooperation, mutual trust between colleagues to provide open communication without discrimination and fear of expressing themselves13. The main contribution to exercising freedom of expression is the autonomy to create and recreate the environment and relationships, taking into account colleagues’ knowledge and giving meaning to multidisciplinary work13.

In this study, the following stand out as sources of pleasure: pride in what I do and solidarity with colleagues. This shows that there is a good relationship between team members that can be influenced by multidisciplinary communication14. Moreover, it may indicate that there are some moments in which everyone can express their worries and discuss decision making to strengthen themselves as a team15.

Workers seek to provide quality assistance and resolve due to good affinity and relationship with colleagues and users16,11. This relationship enables recognition and satisfaction at work, providing a sense of pride in practicing what they enjoy and observing good clinical outcomes from users’ perspective17,11.

Professional burnout and lack of recognition influence suffering at work because they show greater tendencies to stress and indignation. These problems are associated with exhaustive daily life, high demand for care, emotional and physical burnout, conflicts due to shortage of materials and staff13. No matter how tired the worker is, the recognition of colleagues, management, and users provides pleasure when engaging in work activities11.

Among the associations, there was a significant association between professional burnout in women, number of education years up to five years, work accident and profession of community health workers. The other two factors, professional achievement and lack of recognition, were only related to the work accident variable.

In this study, it was found that women tend to have greater professional burnout, which may be justified by the performance of multiple functions, besides their additional activities such as household activities and maternity1. In addition, education time of up to five years may influence burnout, taking into account that these professionals are in the process of insertion and adaptation in the workplace and are gradually integrating with the team and sector activities7.

The associations of pleasure and suffering factors showed that professionals who had had work accidents before had greater professional burnout and a lack of recognition. In contrast, those who had not had an accident had greater professional achievement. This finding may be related to work overload and mental and physical burnout due to long working hours16.

Working conditions are sources causing suffering for workers, which are related to physical space, low pay, human and material resources. A study conducted with PHC nurses in São Paulo, Brazil evaluated the material and professional resources as inadequate18. These factors may affect the development of suffering and later stress, physical, mental and emotional burnout, besides affecting the assistance provided to users18.

Professional burnout was prevalent among community workers, which may be related to the unit's work process. PHC work is characterized by assisting, in large part, the communities that need greater preventive care and health promotion, as well as social and economic attention19,20. Community workers are responsible for articulating users’ demands for PHC assistance. This is due to the proximity and bond with the community20, which reflects the burnout of community workers, who end up experiencing situations of pleasure as well as suffering.

In general, these findings point out the need to change the form of organization at work, considering the large demands of tasks to be performed in a short period of time and the weaknesses of staff sizing18.

From this perspective, it is essential to seek both individual and group strategies that facilitate the experience and coping with difficult situations. In order to make the environment more pleasant and less painful to perform activities6, adjustments of staff sizing are suggested to meet the large demand of users.

CONCLUSIONS

The results showed that professional achievement, considered as an indicator of pleasure, professional burnout and lack of recognition, which are indicators of suffering, were evaluated as critical. Regarding freedom of expression, considered an indicator of pleasure, it was assessed as satisfactory, indicating that workers feel free to express their thoughts.

Based on the analysis of these factors, it can be observed that the “pride in what I do” and “solidarity among colleagues” items among the experiences of pleasure indicators, and “stress” and “indignation” among the experiences that indicate suffering at work, showed the highest averages in workers’ evaluation.

In view of this, it is necessary to implement strategies aimed at workers’ wellness. For such, campaigns of self-esteem and pleasure at work are suggested as these actions may generate quality indicators to the operating environment, focusing on measuring their effectiveness in a given period of application.

Management must meet the needs of human labor by providing infrastructure improvements focused on ergonomics, material availability, and policymaking to improve work environment. The aim is to increase the service quality index, making it more pleasant with a lower level of burnout.

Thus, this study will help managers identify pleasure and suffering indicators in workers, as well as contribute to conducting research focusing on strategies to tackle suffering and actions that promote pleasure at work.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES