Rev Cuid. 2025; 16(2): 4614

Abstract

Introduction: Lifestyles comprise the set of habits and behaviors that influence individuals’ health and well-being. When not properly adopted, they can contribute to the development of chronic diseases and a decline in quality of life. Objective: To describe health-promoting lifestyles among nursing students at a public university in the Province of Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 2024. Materials and Methods: An analytical, cross-sectional, quantitative study was conducted. The study included 314 nursing students who completed Nola Pender’s Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile - II. For the inferential analysis, Student’s t-tests, ANOVA, and Pearson’s correlation test were applied. Results: Respondents had a mean age of 27.04 years (SD = 8.11); most were female (86.62%), single (76.43%), childless (73.25%), working (55.41%), and enrolled in the fourth year of the program (24.52%). Healthy ratings were observed in the dimensions of Spiritual growth and Interpersonal Relations, while the remaining dimensions were rated as unhealthy. The average lifestyle score was 124.97 points (SD = 20.49), equivalent to 60.08% of the instrument’s total score. A total of 78.66% of respondents had a lifestyle categorized as regular. Discussion: It is necessary to implement interventions aimed at strengthening self-care practices among nursing students and identify the associated factors. Conclusion: Most of the respondents exhibited a regular lifestyle with high levels of physical inactivity, overweight, poor dietary habits, and inadequate stress management.

Keywords: Healthy Lifestyle; Students; Nursing; Self Care; Health Promotion; Education, Nursing.

Resumen

Introducción: Los estilos de vida son el conjunto de hábitos y costumbres que influyen en la salud y bienestar de las personas; no aplicarlos adecuadamente puede llevar al desarrollo de enfermedades crónicas y un deterioro en la calidad de vida. Objetivo: Describir los estilos de vida promotores de salud en estudiantes de Enfermería de una universidad pública en la provincia de Buenos Aires, Argentina en 2024. Materiales y Métodos: Estudio analítico, transversal y cuantitativo. Participaron 314 estudiantes de Enfermería quienes completaron el instrumento Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile – II de Nola Pender. Para el análisis inferencial se aplicaron las pruebas T de Student, ANOVA y prueba de correlación de Pearson. Resultados: Los encuestados tuvieron una edad promedio de 27,04 años (DE: 8,11), y en su mayoría pertenecen al género femenino (86,62%), solteros (76,43%), sin hijos (73,25%), laboralmente activos (55,41%) y cursando el cuarto año del plan de estudios (24,52%). Se encontró una valoración saludable en las dimensiones Autorrealización y Relaciones Interpersonales, y poco saludable en las demás. El estilo de vida obtuvo un puntaje promedio de 124,97 puntos (DE=20,49) equivalente al 60,08% del puntaje total del instrumento. El 78,66% de los encuestados presentaron un estilo de vida categorizado como regular. Discusión: Se requiere implementar intervenciones orientadas a fortalecer las prácticas de autocuidado en los estudiantes de Enfermería e identificar los factores relacionados. Conclusión: En su mayoría los encuestados presentaron un estilo de vida regular con altos índices de inactividad física, sobrepeso, hábitos de alimentación deficientes e inadecuado manejo del estrés.

Palabras Clave: Estilo de Vida Saludable; Estudiantes; Enfermería; Autocuidado; Promoción de la Salud; Educación en Enfermería.

Resumo

Introdução: Estilos de vida são o conjunto de hábitos e costumes que influenciam a saúde e o bem-estar das pessoas; a não implementação adequada pode levar ao desenvolvimento de doenças crônicas e à deterioração da qualidade de vida. Objetivo: Descrever os estilos de vida promotores da saúde de estudantes de enfermagem de uma universidade pública na província de Buenos Aires, Argentina, em 2024. Materiais e Métodos: Estudo analítico, transversal e quantitativo. Participaram 314 estudantes de enfermagem que preencheram o Perfil de Estilo de Vida Promotor da Saúde – II de Nola Pender. Testes T de Student, ANOVA e correlação de Pearson foram utilizados para análise inferencial. Resultados: Os entrevistados tinham idade média de 27.04 anos (DP: 8.11), sendo a maioria do sexo feminino (86.62%), solteira (76.43%), sem filhos (73.25%), empregada (55.41%) e cursando o quarto ano de estudo (24.52%). Foi encontrada avaliação saudável nas dimensões Autorrealização e Relações Interpessoais, e não saudável nas demais. O estilo de vida obteve escore médio de 124.97 pontos (DP = 20.49), equivalente a 60.08% do escore total do instrumento. 78.66% dos respondentes apresentaram estilo de vida categorizado como regular. Discussão: Faz-se necessária a implementação de intervenções que visem ao fortalecimento das práticas de autocuidado em estudantes de enfermagem e à identificação dos fatores relacionados. Conclusão: A maioria dos respondentes apresentou estilo de vida regular, com altos índices de inatividade física, sobrepeso, maus hábitos alimentares e manejo inadequado do estresse.

Palavras-Chave: Estilo de Vida Saudável; Estudantes; Enfermagem; Autocuidado; Promoção da Saúde; Educação em Enfermagem.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO)1 defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” Maintaining an optimal state of health depends on various factors grouped under the concept of lifestyle (LS), which includes a balanced diet, adequate rest, regular physical activity, health monitoring and control, abstaining from tobacco and drug use, and low or no alcohol consumption, among others2. A LS is considered health-promoting when it comprises habits and practices that support physical, mental, and social well-being. Conversely, an inadequate lifestyle is considered a risk factor for the development of chronic noncommunicable cardiometabolic diseases that adversely affect individuals' quality of life and well-being3,4.

Academic life has been identified as a factor that significantly impacts the maintenance of a healthy LS, as it often limits the time available for proper nutrition, physical activity, rest, and self-care5. In the case of students in health-related disciplines, they acquire knowledge intended to encourage health-promoting behaviors in their patients. However, it has been observed that these habits are frequently not applied in their own daily lives, negatively affecting their academic performance and overall well-being6-11.

In Argentina, the curriculum of the Bachelor's Degree in Nursing, declared a degree of public interest since 2013, has specific characteristics, including a heavy academic workload and high demands (of time and effort) in hospital and community practice settings. The nursing program has a minimum duration of four years, often extending to five years in public higher education institutions. The curriculum is organized into two cycles: upon completing the third year, students obtain the title of Nurse, and at the end of the final year (fourth or fifth, depending on the institution), they obtain the Bachelor of Science in Nursing degree. These features are relevant when analyzing self-care patterns within this population. Furthermore, the complex socioeconomic context of the Argentine Republic, marked by high inflation rates and steadily declining purchasing power, prompts students to take on heavy workloads to earn an income that allows them to meet their basic needs while keeping up with the academic demands of the program, affecting the time available for self-care. In recent years, there has been a growing body of research focused on describing the LS of nursing students, revealing a high prevalence of risk factors for both communicable and non-communicable diseases. In Argentina, the 4th National Survey of Risk Factors (ENFR, by its acronym in Spanish)12 reported a high prevalence of risk factors, such as smoking (22.2%), overweight and obesity (66.1%), excessive alcohol consumption (13.3%), and low intake of fruits and vegetables (6.0%). A multicenter study conducted in Argentina5, which included 1,718 students from eight higher education institutions, identified a high level of unhealthy habits, with 68.92% of students exhibiting what was categorized as a “regular” LS. Similar findings have been corroborated in other studies involving comparable populations13,14.

Nola Pender, the author of the Health Promotion Model, addresses in her theory aspects related to individuals’ decisions to adopt self-care behaviors. These aspects include expectations about one’s health status, knowledge, beliefs, and previous experiences regarding the adoption of habits associated with a healthy LS10. This theorist proposes four conditions for the adoption of health-promoting LS: attention (interest in the observed habits), retention (the ability to remember what has been learned), reproduction (the ability to replicate the observed behaviors), and motivation (the elements that drive the implementation of the habit). Based on this, it would be expected that students, particularly those enrolled in nursing programs, would incorporate the health-promoting behaviors they learn into their own daily lives. However, the evidence reported in the literature is contrasting5,11,13,14.

It is therefore necessary to conduct studies that evaluate the extent to which nursing students implement health-promoting LS, as well as the factors associated with their implementation, in order to design intervention plans aimed at their improvement.

Based on the elements previously outlined, the present study aimed to describe health-promoting lifestyles among students enrolled in the Bachelor’s Degree in Nursing at a public university in the province of Buenos Aires, Argentina, during the first four-month period of 2024.

Materials and Methods

A quantitative, analytical, and cross-sectional study was conducted at a public higher education institution in the city of Bahía Blanca, Province of Buenos Aires (Argentina), during the first four-month period of 2024. The target population consisted of 609 students enrolled in the Bachelor of Science in Nursing program. A sample of 314 students (51.55% of the universe) was selected through non-probabilistic convenience sampling. This sample ensured a 95% confidence level, a margin of error of less than 5%, and adequate representation of students from all years of the nursing program. The randomization process was supported by the Working in Epidemiology tool (WinEpi ©2006).

Students enrolled and actively attending from the first to the fifth year of the Bachelor of Science in Nursing program who voluntarily agreed to participate by signing the informed consent form were included in the study. Forms that were incorrectly completed or had missing data were excluded.

To collect information, the Health Promoting Lifestyle Profile II (HPLP-II), an instrument developed by Nola Pender under her Health Promotion Model, was used. This tool has a reported Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.70 to 0.935,11,14. The instrument consists of 52 items grouped into six dimensions: Health Responsibility, Nutrition, Spiritual growth, and Interpersonal Relations (nine items each); and Physical Activity and Stress Management (eight items each). Responses are recorded on a four-point Likert scale: Never (1 point), Sometimes (2 points), Often (3 points), and Routinely (4 points). The total score of the 52 items allows for categorizing the lifestyle as unhealthy (52–104 points), regular (105–156 points), or healthy (157–208 points). Likewise, each dimension is also classified as healthy (≥61% of the maximum score for that dimension) or unhealthy (< 60%) (see Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of lifestyle dimension scores

X

Table 1. Characteristics of lifestyle dimension scores

| Dimension |

Items |

Unhealthy |

Healthy |

| Health responsibility |

3, 9, 15, 21, 27, 33, 39, 45, and 51 |

9 to 22 |

23 to 36 |

| Physical activity |

4, 10, 16, 22, 28, 34, 40, and 46 |

8 to 19 |

20 to 32 |

| Nutrition |

2, 8, 14, 20, 26, 32, 38, 44, and 50 |

9 to 22 |

23 to 36 |

| Spiritual growth |

6, 12, 18, 24, 30, 36, 42, 48, and 52 |

9 to 22 |

23 to 36 |

| Interpersonal relations |

1, 7, 13, 19, 25, 31, 37, 43, and 49 |

9 to 22 |

23 to 36 |

| Stress management |

5, 11, 17, 23, 29, 35, 41, and 47 |

8 to 19 |

20 to 32 |

Six questions were included to collect sociodemographic and academic characteristics of the students (age, gender, marital status, number of children, employment status, and year of study), along with Body Mass Index (BMI)6. The instrument was uploaded to Google Forms and distributed through the institutional campus platform and participants’ email addresses.

For the analysis, the data were exported into a Microsoft Excel matrix and processed using the Infostat v/L software. Descriptive statistics included absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables, as well as measures of central tendency and dispersion (mean and standard deviation) for quantitative variables. For inferential analysis, since the variables followed a normal distribution (W = 0.00; p = 0.859), Student’s t-test (for comparing means between two groups), ANOVA (for comparing means across three or more groups), and Pearson’s correlation coefficient (for relationships between quantitative variables) were used. A significance level of p = 0.05 was established.

The study was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee (Resolution 0032, October 2023). Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained. Data collection ensured participant anonymity, as no identifying personal information was gathered. The full dataset is available for free access and consultation on Mendeley Data15.

Results

A total of 314 undergraduate nursing students participated, with a mean age of 27.04 years (SD: 8.11). The majority were female (86.62%), single (76.43%), without children (73.25%), working (55.41%), and enrolled in the fourth year of the program (24.52%). The average Body Mass Index (BMI) was 25.86 kg/m² (SD = 6.08), with 49.04% of participants classified as having a normal weight (see Table 2).

It was found that the item “Attend educational programs on personal health care” from the Health Responsibility dimension had the lowest mean score (1.42; SD = 0.66), while the item “Touch and am touched by people I care about” from the Interpersonal Relations dimension had the highest mean score (3.29; SD = 0.75) (see Table 3).

Table 2. Sample characteristics

X

Table 2. Sample characteristics

| Variable |

% (n) |

| Age. Mean (SD) |

8.11 (27.04) |

| Gender |

|

| Female |

86.62 (272) |

| Male |

12.42 (39) |

| Other |

0.96 (3) |

| Marital status |

|

| Single |

76.43 (240) |

| Cohabiting or married |

21.34 (67) |

| Divorced or widowed |

2.23 (7) |

| Children |

|

| Yes |

26.75 (84) |

| No |

73.25 (230) |

| Working |

|

| Yes |

55.41 (174) |

| No |

44.59 (140) |

| Year of study |

|

| First |

19.75 (62) |

| Second |

20.38 (64) |

| Third |

22. 93 (72) |

| Fourth |

24.52 (77) |

| Fifth |

12.42 (39) |

| Body Mass Index |

|

| Underweight |

4.78 (15) |

| Normal weight |

49.04 (154) |

| Overweight |

29.94 (94) |

| Grade 1 obesity |

9.55 (30) |

| Grade 2 obesity |

3.82 (12) |

| Grade 3 obesity |

2.87 (9) |

| Total |

100.00 (314) |

Table 3. Mean and standard deviation of items in the health-promoting lifestyle profile among nursing students

X

Table 3. Mean and standard deviation of items in the health-promoting lifestyle profile among nursing students

| Item |

Mean ± SD |

| Discuss my problems and concerns with people close to me. |

2.59 ± 0.75 |

| Choose a diet low in fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol |

2.24 ± 0.81 |

| Report any unusual signs or symptoms to a physician or other health professional. |

2.41 ± 0.81 |

| Follow a planned exercise program. |

2.18 ± 0.99 |

| Get enough sleep. |

2.18 ± 0.71 |

| Feel I am growing and changing in positive ways. |

2.72 ± 0.75 |

| Praise other people easily for their achievements. |

3.15 ± 0.72 |

| Limit use of sugars and food containing sugar (sweets). |

2.29 ± 0.93 |

| Read or watch TV programs about improving health. |

1.93 ± 0.86 |

| Exercise vigorously for 20 or more minutes at least three times a week (such as brisk walking, bicycling, aerobic dancing, using a stair climber). |

2.41 ± 1.06 |

| Take some time for relaxation each day. |

2.21 ± 0.74 |

| Believe that my life has purpose. |

3.04 ± 0.79 |

| Maintain meaningful and fulfilling relationships with others. |

3.08 ± 0.77 |

| Eat 6-11 servings of bread, cereal, rice and pasta each day. |

1.79 ± 0.81 |

| Question health professionals in order to understand their instructions. |

2.62 ± 0.8 |

| Take part in light to moderate physical activity (such as sustained walking 30-40 minutes 5 or more times a week). |

2.32 ± 0.91 |

| Accept those things in my life which I cannot change. |

2.59 ± 0.76 |

| Look forward to the future. |

3.1 ± 0.73 |

| Spend time with close friends. |

2.68 ± 0.79 |

| Eat 2-4 servings of fruit each day. |

2.45 ± 0.91 |

| Get a second opinion when I question my health care provider's advice. |

2.08 ± 0.78 |

| Take part in leisure-time (recreational) physical activities (such as swimming, dancing, etc.). |

1.95 ± 0.92 |

| Concentrate on pleasant thoughts at bedtime. |

2.29 ± 0.78 |

| Feel content and at peace with myself. |

2.62 ± 0.82 |

| Find it easy to show concern, love and warmth to others. |

2.81 ± 0.94 |

| Discuss my health concerns with health professionals. |

2.51 ± 0.85 |

| Eat 3-5 servings of vegetables each day. |

2.31 ± 0.86 |

| Do stretching exercises at least 3 times per week. |

2.12 ± 0.99 |

| Use specific methods to control my stress |

1.71 ± 0.84 |

| Work toward long-term goals in my life |

2.92 ± 0.74 |

| Touch and am touched by people I care about. |

3.29 ± 0.75 |

| Eat 2-3 servings of milk, yogurt, or cheese each day. |

2.43 ± 0.89 |

| Inspect my body at least monthly for physical changes/danger signs. |

2.52 ± 0.88 |

| Get exercise during usual daily activities (such as walking during lunch or using stairs instead of elevators). |

2.29 ± 0.88 |

| Balance time between work and play. |

2.19 ± 0.74 |

| Find each day interesting and challenging. |

2.42 ± 0.81 |

| Find ways to meet my needs for intimacy. |

2.48 ± 0.78 |

| Eat only 2-3 servings from the meat, poultry, fish, dried beans, eggs, and nuts group each day. |

2.45 ± 0.84 |

| Ask for information from health professionals about how to take good care of myself. |

2.12 ± 0.81 |

| Check my pulse rate when exercising. |

1.79 ± 0.95 |

| Practice relaxation or meditation for 15-20 minutes daily. |

1.47 ± 0.75 |

| Am aware of what is important to me in life. |

3.02 ± 0.73 |

| Get support from a network of caring people. |

2.63 ± 0.81 |

| Read labels to identify nutrients, fats, and sodium content in packaged food. |

2.01 ± 1.04 |

| Attend educational programs on personal health care |

1.42 ± 0.66 |

| Reach my target heart rate when exercising |

1.67 ± 0.83 |

| Pace myself to prevent tiredness. |

1.87 ± 0.72 |

| Feel connected with some force greater than myself. |

2.24 ± 1.09 |

| Settle conflicts with others through discussion and compromise. |

2.95 ± 0.76 |

| Eat breakfast. |

2.85 ± 1.01 |

| Seek guidance or counseling when necessary. |

2.85 ± 0.79 |

| Expose myself to new experiences and challenges. |

2.74 ± 0.79 |

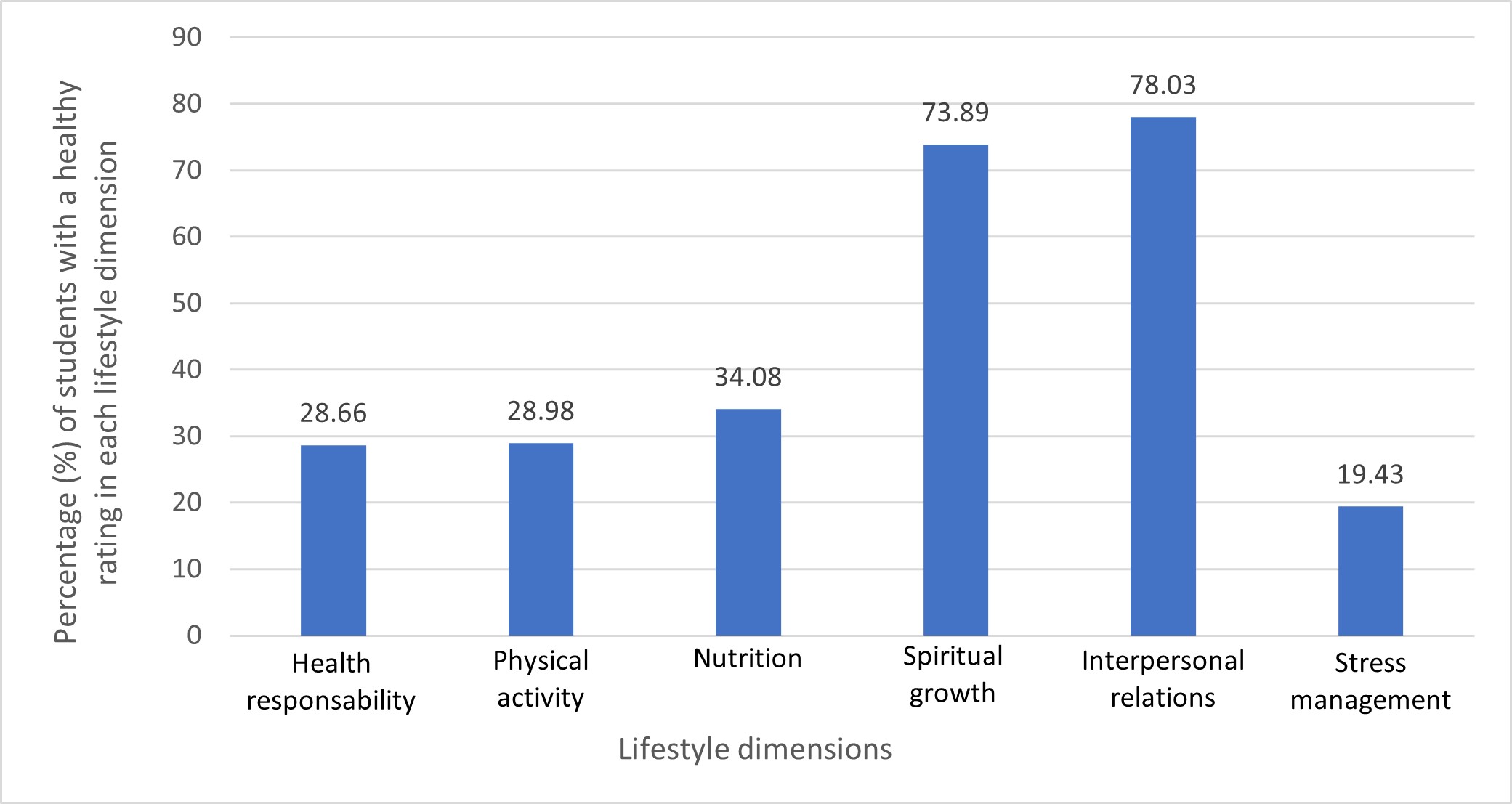

When analyzing the dimensions of lifestyle, Interpersonal Relations was the best rated with a mean of 25.66 points (95% CI = 25.15-26.16), and 78.03% of participants were categorized as healthy in this dimension. In contrast, Stress Management showed the lowest scoring with a mean of 16.51 points (95% CI = 16.13-16.88), and only 19.43% of respondents were classified as healthy in this area (see Figure 1).

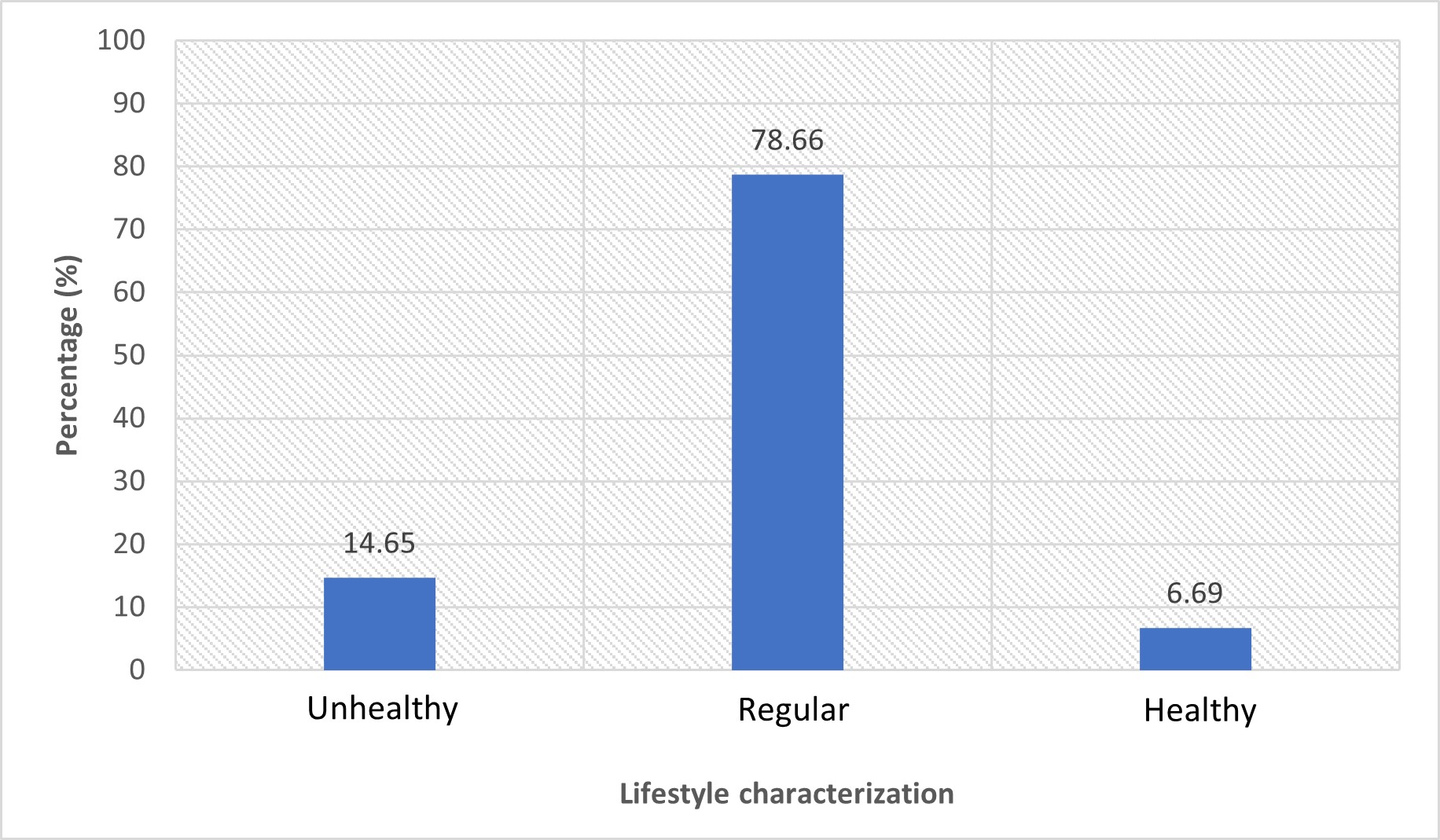

A total of 78.66% (n=247) of the participants presented a lifestyle categorized as regular (see Figure 2), with an overall mean lifestyle score of 124.97 points (SD = 20.49, 95% CI = 122.70-127.25), equivalent to 60.08% of the total possible score on the instrument.

Inferential analysis revealed a negative correlation between age and the Physical Activity dimension (r = –0.15, p = 0.006), and a positive correlation between age and BMI (r = 0.31, p < 0.001).

When comparing the mean scores of the LS dimensions against students’ sociodemographic and academic variables, the following findings were observed: higher scores (better lifestyle) in the Health Responsibility dimension among female students (p=0.005); higher scores in Physical Activity among students without children (p=0.015), those who were not working (p = 0.024), and those taking third-year courses of the study plan (p< 0.001); and better Stress Management among students without children (p=0.023), and those who were not working (p=0.008). Likewise, lower score means in the Nutrition dimension were observed among students taking first-year courses (p=0.038) (see Table 4). The BMI score showed a low, negative correlation with the Nutrition dimension (r=-0.12, p=0.027).

Table 4. Associations between lifestyle dimensions and sociodemographic and educational variables

X

Table 4. Associations between lifestyle dimensions and sociodemographic and educational variables

| Categories |

HR |

PA |

NT |

SG |

IR |

SM |

LS |

| Gender |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Female |

20.57* |

16.56 |

21.05 |

24.95 |

25.86 |

16.54 |

125.52 |

| Male |

18.38 |

17.97 |

20.54 |

24.38 |

24.46 |

16.49 |

122.23 |

| Marital status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Single |

20.34 |

17.00 |

21.00 |

24.63 |

25.76 |

16.65 |

125.39 |

| Cohabiting or married |

20.01 |

15.94 |

21.07 |

25.43 |

25.46 |

15.99 |

123.91 |

| Children |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

20.36 |

15.55 |

20.48 |

25.38 |

25.4 |

15.87 |

123.04 |

| No |

20.23 |

17.14* |

21.2 |

24.62 |

25.75 |

16.74* |

125.68 |

| Working |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

20.25 |

16.13 |

20.72 |

25.25 |

25.79 |

16.05 |

124.18 |

| No |

20.28 |

17.45* |

21.33 |

24.29 |

25.49 |

17.08* |

125.96 |

| Year of study |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| First |

19.15 |

15.21 |

19.44* |

24.16 |

25 |

16.27 |

119.23 |

| Second |

20.39 |

18.06 |

21.52 |

23.95 |

25 |

16.72 |

125.64 |

| Third |

20.57 |

18.49* |

21.43 |

24.51 |

26.1 |

17.06 |

128.15 |

| Fourth |

20.82 |

15.69 |

21.08 |

25.78 |

25.6 |

16.42 |

125.38 |

| Fifth |

20.18 |

15.67 |

21.77 |

25.97 |

27.08 |

15.69 |

126.36 |

Note: *Statistically significant values. HR: Health responsibility, PA: Physical activity, NT: Nutrition, SG: Spiritual growth, IR: Interpersonal relations, SM: Stress management, and LS: Lifestyle.

Discussion

In the present study, the majority of participants were female, single, childless, working, and enrolled in the fourth year of the nursing program. Respondents were found to have a LS classified as regular. Likewise, a healthier LS was observed among female students, those without children, those exclusively dedicated to their studies, and those in the first cycle of the program (first to third year of the study plan).

These data are consistent with previous literature reporting higher levels of health responsibility among women, greater physical activity, and better stress management among students without children and those not working, likely due to greater time availability and fewer competing responsibilities16-19. At the same time, unhealthy nutritional habits were identified among recently enrolled students in the program, possibly due to a lack of knowledge and awareness about healthy eating.

Age was negatively correlated with the physical activity dimension and positively correlated with BMI. This suggests a decline in physical activity levels with age increase, likely associated with growing responsibilities (such as parenting or a lack of exclusive dedication to studies), which may explain the higher BMI at older ages. While these results contradict other studies reporting higher levels of physical activity among older students18,19, they are consistent with others that have identified a decrease in health accountability with age14.

In the present study, high levels of overweight and obesity were identified among students of the Bachelor's Degree in Nursing. This finding aligns with the high levels of sedentary behavior and poor eating habits reported by nearly three-quarters of participants, consistent with findings from several other studies20,21. However, it contrasts with reports from other student populations that demonstrated more adequate dietary patterns22.

Approximately one-fifth of respondents reported poor stress management, a factor previously associated with the combined demands of academic, social, family, and work responsibilities23-25. Considering that over half of the students were working, one-quarter had children, and most were women, these circumstances added responsibilities associated with these factors.

Finally, LS was classified as regular in 78.66% of the respondents, which coincides with studies conducted among nursing students, where the regular category was reported in approximately one-sixth to one-seventh of participants5,11,14,19,26-28. Undoubtedly, the demands of higher education, particularly in health-related programs, significantly influence students’ self-care patterns. This underscores the need for designing interventions to sustain and improve students’ lifestyles, thereby preventing health deterioration and the entrenchment of unhealthy behaviors that could impact their professional performance. Higher education institutions should establish health-promoting activities involving students, faculty, administrative staff, support personnel, and their families, without reducing their role to the provision of educational services29. The aforementioned aspects align with the Healthy Universities strategy30-33 in the Argentine Republic, which defines such institutions as “those that promote the holistic health of their community by acting on the physical and social environment, the educational process, and the broader community in which they are embedded.”

Limitations

As limitations, the present study was conducted at a single public institution of higher education. Additionally, the specific characteristics of the study population (such as employment status) may not be representative of students in other national or international institutions. Another limitation lies in the use of self-reported measures to assess students’ lifestyles, which may result in response bias, as participants might report behaviors they perceive as ideal rather than those that accurately represent their behaviors. The sampling method used (convenience sampling) is also a limitation of the study, as it may have led to a possible selection bias.

The study highlights the use of an instrument validated in Argentina and widely employed, as well as the representativeness of the data among students in the nursing program. This work provides an updated background for the knowledge of self-care dynamics of Bachelor of Nursing students and how social, demographic, and academic variables influence them. Future studies should explore the impact of lifestyle on quality of life and academic performance, expand the sample size, compare public and private institutions, and identify the limitations to self-care in this population.

Conclusion

The LS of the nursing students was categorized as regular, characterized by unhealthy behaviors such as low responsibility in managing personal health, high levels of physical inactivity, poor dietary habits, and inadequate stress management. Overweight and obesity affected half of the participants, and a correlation was found between BMI and scores in the Nutrition dimension.

Higher mean scores (indicating a healthier lifestyle) were found in the Health Responsibility dimension among women, in the Physical Activity dimension among students without children, those exclusively dedicated to studying, and those enrolled in the third year of the study plan. Likewise, better stress management was observed among students without children and those not working, whereas poorer nutritional habits were reported among students enrolled in the first year of the nursing program.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to the publication of this article.

Financing: This research was supported by the Universidad Nacional del Sur.

References

X

Referencias

Arellano JF, Arlen Pineda E, Ponce ML, Zarco A, Aburto IA, Arellano DU. Academic stress in first year students in the career of Medical Surgeon of the Facultad de Estudios Superiores Zaragoza. UNAM, 2022. Seminars in Medical Writing and Education. 2023;2:37. https://doi.org/10.56294/mw202337

X

Referencias

Canova-Barrios C, Nores RI, Méndez PG, Farfán AB, Moreno LA, Silvestre N de F et al. Estilos de vida de los estudiantes de Enfermería de Argentina. Retos. 2024;56:817-23. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v56.105167

X

Referencias

Canova-Barrios C, Almeida JA, Condori-Aracayo ER, Mansilla MA, Garis DN. Calidad de vida relacionada con la salud en estudiantes de tecnicatura en enfermería. Rev Chil Enferm. 2023;5(2):44–56. https://doi.org/10.5354/2452-5839.2023.72003

X

Referencias

Garces Garces NN, Esteves Fajardo ZI, Santander Villao ML, Mejía Caguana DR, Quito Esteves AC. Relationships between Mental Well-being and Academic Performance in University Students: A Systematic Review. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología - Serie de Conferencias. 2024;3:972. https://doi.org/10.56294/sctconf2024972

X

Referencias

Lermanda Peña C, Sánchez Álvarez C, Oliva Vega E, Astudillo Ganora I. Relationship between risky alcohol consumption and academic performance in students in the health area at a Chilean University. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología. 2024;4:914. https://doi.org/10.56294/saludcyt2024914

X

Referencias

Canova-Barrios C, Vizgarra Y, Abarza D, Cano CB, Méndez PG. Estilos de vida de Estudiantes de Enfermería. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología - Serie de Conferencias. 2023; 2:399. https://doi.org/10.56294/sctconf2023399

X

Referencias

Jiménez DA, Medina ME, Ortigoza A, Canova-Barrios C. Estilos de vida de los estudiantes de Enfermería de una institución pública de Tucumán, Argentina. Ibero-American Journal of Health Science Research. 2024;4(1):52-58. https://doi.org/10.56183/iberojhr.v4i1.606

X

Referencias

Fernández J, Saavedra X, Torres J. Nutritional status in students following a plant-based diet at the Adventist University of Chile. A descriptive study. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología. 2024;4:905. https://doi.org/10.56294/saludcyt2024905

X

Referencias

Cameron DM, Muratore F, Tower M, Eades CE, Evans JMM. Exploration of health and health behaviours of undergraduate nursing students: a multi-methods study in two countries. Contemp Nurse. 2022;58(5-6):473-483. https://doi.org/10.1080/10376178.2022.2085128

X

Referencias

Shekhar R, Prasad N, Singh T. Lifestyle factors influencing medical and nursing student's health status at the rural health-care institute. J Educ Health Promot. 2022;11(1):21. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_206_21

X

Referencias

Sánchez-Ojeda MA, Roldán C, Melguizo-Rodríguez L, de Luna-Bertos E. Analysis of the Lifestyle of Spanish Undergraduate Nursing Students and Comparison with Students of Other Degrees. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(9):5765. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095765

X

Referencias

Ttito-Vilca SA, Estrada-Araoz EG, Mamani-Roque M. Lifestyle in students from a private university: A descriptive study. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología. 2024;4:630. https://doi.org/10.56294/saludcyt2024630

X

Referencias

Arrigoni C, Grugnetti AM, Caruso R, Dellafiore F, Borelli P, Cenzi M, et al. Describing the health behaviours of future nurses: a cross-sectional study among Italian nursing students. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(3):e2020068. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v91i3.8338

X

Referencias

Bautista-Coaquira MH, Rodríguez-Quiroz MZ. Correlación entre el estilo de vida y nivel de estrés en estudiantes de enfermería de una universidad peruana. Rev Peru Med Integr. 2021;6(4):102-109. https://doi.org/10.26722/rpmi.2021.v6n4.34

X

Referencias

Llorente Pérez YJ, Herrera Herrera JL, Hernández Galvis DY, Padilla Gómez M, Padilla Choperena CI. Estrés académico en estudiantes de un programa de Enfermería - Montería 2019. Rev Cuid. 2020;11(3):e1108. https://doi.org/10.15649/cuidarte.1108

X

Referencias

Davarinejad O, Hosseinpour N, Majd TM, Golmohammadi F, Radmehr F. The relationship between Life Style and mental health among medical students in Kermanshah. J Educ Health Promot. 2020;9(1):264. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_534_20

X

Referencias

Ríos NB, Arteaga CM, González Arias Y, Martínez AA, Nogawa MH, Quinteros AM, et al. Self-medication in nursing students. Interdisciplinary Rehabilitation / Rehabilitacion Interdisciplinaria. 2024;4:71. https://doi.org/10.56294/ri202471

X

Referencias

Fernández J, Saavedra X, Torres J. Nutritional status in students following a plant-based diet at the Adventist University of Chile. A descriptive study. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología. 2024;4:905. https://doi.org/10.56294/saludcyt2024905

X

Referencias

Araneo J, Escudero FI, Muñoz Arbizu MA, Trivarelli CB, Van Den Dooren MC, Lichtensztejn M, et al. Wellness and Integrative Health Education Campaign by undergraduate students in Music Therapy. Community and Interculturality in Dialogue. 2023;3:117. https://doi.org/10.56294/cid2023117

X

Referencias

Barrera Loayza SK, Altamirano Mena MJ, Medina Naranjo GR. Recommendation of public policies to improve the lifestyles of nursing students at the Regional Autonomous University of the Andes. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología - Serie de Conferencias. 2023;2:1114. https://doi.org/10.56294/sctconf20231114

X

Referencias

Canova-Barrios CJ, Robledo GP, Segovia AB, Manzur KM. Health-related quality of life and self-care practices in nursing students. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología - Serie de Conferencias. 2023;2:516. https://doi.org/10.56294/sctconf2023516

X

Referencias

Robaina Castillo JI. Cultural competence in medical and health education: an approach to the topic. Seminars in Medical Writing and Education. 2022;1:13. https://doi.org/10.56294/mw202213

-

Organización Mundial de la Salud. Constitución de la OMS, 1945. Consulta: Octubre 13, 2024. Disponible en: https://www.who.int/es/about/governance/constitution

-

Ministerio de Salud Argentina. Hábitos saludables, factores de riesgo y enfermedades no transmisibles. Consulta: Noviembre 3, 2024. Disponible en: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/salud/habitos-saludables

-

Arellano JF, Arlen Pineda E, Ponce ML, Zarco A, Aburto IA, Arellano DU. Academic stress in first year students in the career of Medical Surgeon of the Facultad de Estudios Superiores Zaragoza. UNAM, 2022. Seminars in Medical Writing and Education. 2023;2:37. https://doi.org/10.56294/mw202337

-

Suarez Villa ME, Navarro Agamez MJ, Caraballo Robles DR, López Mozo LV, Recalde Baena AC. Estilos de vida relacionados con factores de riesgo cardiovascular en estudiantes Ciencias de la Salud. Ene. 2020;14(3):e14307. https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?pid=S1988-348X2020000300007&script=sci_arttext&tlng=en

-

Canova-Barrios C, Nores RI, Méndez PG, Farfán AB, Moreno LA, Silvestre N de F et al. Estilos de vida de los estudiantes de Enfermería de Argentina. Retos. 2024;56:817-23. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v56.105167

-

Canova-Barrios C, Almeida JA, Condori-Aracayo ER, Mansilla MA, Garis DN. Calidad de vida relacionada con la salud en estudiantes de tecnicatura en enfermería. Rev Chil Enferm. 2023;5(2):44–56. https://doi.org/10.5354/2452-5839.2023.72003

-

Canova-Barrios C. Estilo de vida de estudiantes universitarios de enfermería de Santa Marta, Colombia. Rev. Colomb. Enferm. 2017;14:23-32. https://doi.org/10.18270/rce.v14i12.2025

-

Garces Garces NN, Esteves Fajardo ZI, Santander Villao ML, Mejía Caguana DR, Quito Esteves AC. Relationships between Mental Well-being and Academic Performance in University Students: A Systematic Review. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología - Serie de Conferencias. 2024;3:972. https://doi.org/10.56294/sctconf2024972

-

Lermanda Peña C, Sánchez Álvarez C, Oliva Vega E, Astudillo Ganora I. Relationship between risky alcohol consumption and academic performance in students in the health area at a Chilean University. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología. 2024;4:914. https://doi.org/10.56294/saludcyt2024914

-

Aristizábal Hoyos GP, Blanco Borjas DM, Sánchez Ramos A, Ostiguín Meléndez RM. El modelo de promoción de la salud de Nola Pender: Una reflexión en torno a su comprensión. Enferm Univ. 2011;8(4):16-23. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1665-70632011000400003&lng=es.

-

Canova-Barrios C, Vizgarra Y, Abarza D, Cano CB, Méndez PG. Estilos de vida de Estudiantes de Enfermería. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología - Serie de Conferencias. 2023; 2:399. https://doi.org/10.56294/sctconf2023399

-

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos (INDEC). 4ta Encuesta Nacional de Factores de Riesgo: Resultados definitivos, 2019. Consulta: Octubre 19, 2024. Disponible en: https://www.indec.gob.ar/ftp/cuadros/publicaciones/enfr_2018_resultados_definitivos.pdf

-

Jiménez DA, Medina ME, Ortigoza A, Canova-Barrios C. Estilos de vida de los estudiantes de Enfermería de una institución pública de Tucumán, Argentina. Ibero-American Journal of Health Science Research. 2024;4(1):52-58. https://doi.org/10.56183/iberojhr.v4i1.606

-

Ortigoza A, Canova-Barrios C. Estilos de vida de estudiantes de la Escuela Universitaria de Enfermería de la Universidad Nacional de Tucumán, Argentina. Finlay. 2023;13(2):199-208. http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2221-24342023000200199

-

Canova-Barrios C, Mangano MA, Mercado SL. Health-promoting lifestyles in nursing students from Argentina. 2024. Mendeley Data, V1. https://doi.org/10.17632/gb7cc9t2vx.1

-

Health Education Unit. Life-styles and health. Soc Sci Med. 1986;22(2):117-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(86)90060-2

-

Fernández J, Saavedra X, Torres J. Nutritional status in students following a plant-based diet at the Adventist University of Chile. A descriptive study. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología. 2024;4:905. https://doi.org/10.56294/saludcyt2024905

-

Cameron DM, Muratore F, Tower M, Eades CE, Evans JMM. Exploration of health and health behaviours of undergraduate nursing students: a multi-methods study in two countries. Contemp Nurse. 2022;58(5-6):473-483. https://doi.org/10.1080/10376178.2022.2085128

-

Shekhar R, Prasad N, Singh T. Lifestyle factors influencing medical and nursing student's health status at the rural health-care institute. J Educ Health Promot. 2022;11(1):21. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_206_21

-

Sánchez-Ojeda MA, Roldán C, Melguizo-Rodríguez L, de Luna-Bertos E. Analysis of the Lifestyle of Spanish Undergraduate Nursing Students and Comparison with Students of Other Degrees. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(9):5765. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19095765

-

Ttito-Vilca SA, Estrada-Araoz EG, Mamani-Roque M. Lifestyle in students from a private university: A descriptive study. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología. 2024;4:630. https://doi.org/10.56294/saludcyt2024630

-

Arrigoni C, Grugnetti AM, Caruso R, Dellafiore F, Borelli P, Cenzi M, et al. Describing the health behaviours of future nurses: a cross-sectional study among Italian nursing students. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(3):e2020068. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v91i3.8338

-

Bautista-Coaquira MH, Rodríguez-Quiroz MZ. Correlación entre el estilo de vida y nivel de estrés en estudiantes de enfermería de una universidad peruana. Rev Peru Med Integr. 2021;6(4):102-109. https://doi.org/10.26722/rpmi.2021.v6n4.34

-

Cruz Carabajal D, Ortigoza A, Canova-Barrios C. Estrés académico en los estudiantes de Enfermería. Rev Esp Edu Med. 2024;5(2). https://doi.org/10.6018/edumed.598841

-

Llorente Pérez YJ, Herrera Herrera JL, Hernández Galvis DY, Padilla Gómez M, Padilla Choperena CI. Estrés académico en estudiantes de un programa de Enfermería - Montería 2019. Rev Cuid. 2020;11(3):e1108. https://doi.org/10.15649/cuidarte.1108

-

Davarinejad O, Hosseinpour N, Majd TM, Golmohammadi F, Radmehr F. The relationship between Life Style and mental health among medical students in Kermanshah. J Educ Health Promot. 2020;9(1):264. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_534_20

-

Ríos NB, Arteaga CM, González Arias Y, Martínez AA, Nogawa MH, Quinteros AM, et al. Self-medication in nursing students. Interdisciplinary Rehabilitation / Rehabilitacion Interdisciplinaria. 2024;4:71. https://doi.org/10.56294/ri202471

-

Fernández J, Saavedra X, Torres J. Nutritional status in students following a plant-based diet at the Adventist University of Chile. A descriptive study. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología. 2024;4:905. https://doi.org/10.56294/saludcyt2024905

-

Araneo J, Escudero FI, Muñoz Arbizu MA, Trivarelli CB, Van Den Dooren MC, Lichtensztejn M, et al. Wellness and Integrative Health Education Campaign by undergraduate students in Music Therapy. Community and Interculturality in Dialogue. 2023;3:117. https://doi.org/10.56294/cid2023117

-

Ministerio de Salud Argentina. Estrategia de Universidades Saludables (ENES - US). Consulta: Octubre 25, 2024. Disponible en: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/salud/entornos-saludables/universidades

-

Barrera Loayza SK, Altamirano Mena MJ, Medina Naranjo GR. Recommendation of public policies to improve the lifestyles of nursing students at the Regional Autonomous University of the Andes. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología - Serie de Conferencias. 2023;2:1114. https://doi.org/10.56294/sctconf20231114

-

Canova-Barrios CJ, Robledo GP, Segovia AB, Manzur KM. Health-related quality of life and self-care practices in nursing students. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología - Serie de Conferencias. 2023;2:516. https://doi.org/10.56294/sctconf2023516

-

Robaina Castillo JI. Cultural competence in medical and health education: an approach to the topic. Seminars in Medical Writing and Education. 2022;1:13. https://doi.org/10.56294/mw202213